KORELESS ANNOUNCES DEBUT ALBUM ‘AGOR’

RELEASED 9 JULY 2021 VIA YOUNG

Today Welsh producer Lewis Roberts aka Koreless announces his much-anticipated debut album Agor, due for release 9 July via Young. An album over five years in the making, Agor is announced with the single ‘Joy Squad’, a track that has a life of its own already.

Played by Caribou, Jamie xx and TNGHT in their BBC Radio1 Essential Mixes and with further support from Oli XL and HAAi, ‘Joy Squad’ sparked a mass trawling from fans online for the track Koreless describes as his attempt “to build a club rollercoaster that swallows you up and spits you out.”

The lyric video was directed by Koreless and Mau Morgo. ‘Joy Squad’ will also be released on 12” vinyl ahead of the album release. PRE-ORDER HERE.

There is an idea of hidden depths suggested by the title of Koreless’ debut album. Agor is the Welsh word for open and it’s an apt name for a recording which exists at sensory thresholds, helping guide the listener from one realm to another less visited. It straddles various worlds of dance, ambient and contemporary classical while not sounding like an example of any of them.

PRE-ORDER ‘AGOR’ HERE. Read more about the album in the bio below.

KORELESS BIOGRAPHY

There is an idea of hidden depths suggested by the title of Koreless’ debut album. Agor is the Welsh word for open and it’s an apt name for a recording which exists at sensory thresholds, helping guide the listener from one realm to another less visited. Talking to the artist, Lewis Roberts, it is clear that this idea of a misleadingly calm surface hiding strange depths has been with him for life.

Lewis grew up in the Welsh coastal town of Bangor, in a house built on the banks of a strong flowing estuarine river, spending his youth getting into scrapes sailing near the notoriously dangerous Menai Strait. He took his knowledge of the sea to study Marine Engineering at university. But even while learning about naval studies, he found he was thinking about music: “In the interview for my course, I was asked what would happen if I were to add these three waveforms together. I already knew the answer because I had been playing about with vst synths, with sound waves.”

Because Lewis was already making music and had been for a while. He began creating rudimentary tunes on a big old desktop computer running Cakewalk and VJ, which had been gifted to him by a Café del Mar-loving uncle. This gift proved crucial to Lewis. Rural North Wales can feel very distant from any music scene, but this old computer’s hard drive contained an “encyclopedic body of pop, electronica, chill out and house” ranging from Moby to Lemon Jelly. This cache was essentially Lewis’ introduction to listening to electronic music; it made him realise he wanted to be a music producer, and by the time he left school, Lewis had unlocked the processes that allowed Koreless to be born.

After a series of startling early releases, including his debut EP – 4D – in 2011, he started working with the London based label Young, releasing collaborative work with Sampha and the game-changing ‘Y?gen’ EP later that year. And then he eventually turned his attention to his debut album, which has, admittedly, taken much longer to finish than anyone had envisaged.

Not all of the time since has been spent on his debut – he has worked on various collaborative projects: touring worldwide with his A/V show ‘The Well’ with Emmanuel Biard, performing with Sharon Eyal and Gai Behar’s L-E-V Dance Company at Bold Tendencies in 2019, and not to mention 18 months on and off working with FKA twigs on the critically acclaimed Magdalene album, alongside other high-profile ghost production work. Roberts has also re-imagined Britten’s interlude “Moonlight”, and recently recorded remixes for Perfume Genius and Caribou. Even so, Agor has been a long time in the making. He admits he became obsessive with his own work.

By way of explaining how he spent so long refining every last detail of the album down to the granular level – something he describes as a “sickly obsession” – he quotes the visionary English director and artist Derek Jarman, talking about his work on the film Caravaggio: “I rewrote that script 17 times… it was actually an adventure, and sometimes it got very depressing because it went on and on and on… but actually it was one of the most productive moments of my life”.

He sighs when explaining: “I work very quickly actually, but I’m also very thorough, and find it hard to leave stones unturned. Some of the tracks on this album have been through hundreds of iterations. Getting from the start to the end of the track is such a twisted journey for me. I’m talking about spending 15 hours a day, seven days a week over a period of years.”

One of his radical methods for manipulating sound came from an idea as old as the history of revolutionary electronic music itself: using gear for a job it wasn’t designed for: “Some of the plug-ins I was using weren’t designed for soft synths, they were actually audio repair tools. Podcasters use them to take ‘pops’ out of their audio but if you use that tool 500 times on the same sample you end up with nothing left bar a little glimmer of sound… with methods like this, there was an accidental way of finding my way through the record.”

But, like someone diving through the glassy, becalmed surface of an ocean, only to suffer a wave of sheer existential panic on realising that there are unfathomable depths below, Lewis initially went through something of a crisis that looked like it might fatally capsize the project: “I realised the depth of what I was doing was fractal. There was no actual end to the record in sight. I was obsessed with structure and song as well as texture – they had to be right of course – but once I had the song, that was when the real trouble began. “I would focus on one tiny detail for a day. I would bounce that one element out into a new session and process it a thousand different ways – sometimes literally – having to then judge which the best iteration of that sliver of sound was. Then I would reintroduce that one detail back in and judge how that would then affect everything else. It was quite recursive. The piece would feed back on itself in quite a cybernetic way. But it could have gone on forever.”

Just as it was seeming like the process might never end, sanity, and closure, came finally in the unlikely form of heavy metal. Lewis explains that he decided just to arrange the tracks as they were: “I found a Quora post written by a metalhead describing the best way to structure an album. So I tried his suggestion and I was like, ‘Yeah, it feels really good.’ The record didn’t feel finished until I did that.”

Agor is unlike any other record you’ll hear. It straddles the worlds of ambient and contemporary classical while not sounding like an example of either. The bristling ecstatic trills and rushes of “Yonder” rub up against the euphoric breeze of “Black Rainbow”, “Shellshock” and “Joy Squad,” while “Act(s)” and “Strangers” connect Lewis to a much more distant world: a cybernetic daydream of the composers Benjamin Britten and Edward Elgar. Speaking about Britten, Lewis says: “It makes sense to me on a harmonic level. Compared to other music of that time, his music was ostensibly sweet and followed clear rules, but there’s always something in there that doesn’t quite add up. Something just below the surface, like a crushing inevitability”.

The album’s lead single, “White Picket Fence,” has a spine-tingling anthemic quality to it–with a symphonic melody and a faceless vocal hook. An evidence of Robert’s mass refinement, there are subtle occurrences throughout which he refers to as “ruptures”, where the “bottom falls out of the track and it suddenly collapses into nothingness, like a plane taking off then bursting into the clouds”. It also happens on “Frozen” he explains–”you get some gut-wrenching feeling when the music bursts outwards and collapses into nothing”.

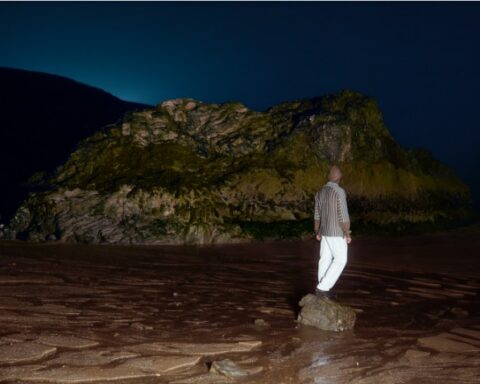

The Agor album cover features artwork by visual artist Daniel Swan. It is the result of a trip to the mountains near Snowdonia, where he and Roberts hiked and built a sequence of home-spun portal machines threading a path through the mountains into the forest. “It’s like the idea of physical objects which link together” Swan says “taking you on a specific geographical journey, acting like lenses to view the landscape differently, kind of an analogue of the way the tracks of the record might change the way you experience specific places in a certain way”.

When he speaks about this attention to detail – of breaking sound apart into tiny fragments and reassembling it in complex patterns – he reaches for a literary comparison: “When it comes to the manipulation of time and the perception of time, I think about the writer JG Ballard. In the novel Crash, he describes an automobile accident in such clinical detail that it stops being a horrific event and becomes like the act of peeling a fig. So in that process even the most violent thing can become fascinating, beautiful and catalogued. I’m interested in slow motion. In violent events occurring so slowly that they become quite beautiful.”

Agor welcomes you to dive into a world of beauty, ecstasy and slow-motion horror, just below the surface.