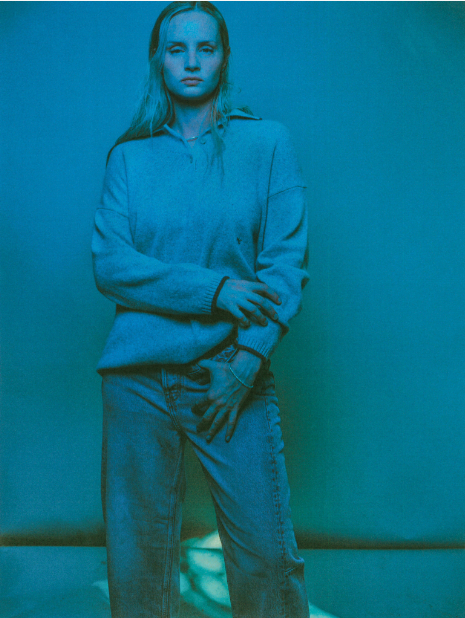

SAM MORTON, the musical duo comprised of singer, songwriter and acclaimed actor and director Samantha Morton and music producer and co-songwriter Richard Russell, has announced details of their highly-anticipated debut album. Titled Daffodils & Dirt, the album will be released on 14 th June via XL Recordings.

Over twelve startling tracks, the pair build a deeply personal musical world that feels simultaneously intimate and delicate yet powerful and tough. The part-autobiographical suite of songs see Russell’s spartan soundscapes providing a rich foundation for Morton’s gorgeous, ethereal vocal, aided by a cast of musical collaborators that include Alabaster DePlume, Laura Groves, Jack Peñate and additional vocalist Ali Campbell (on ‘Broxtowe Girl’).

Despite a lifelong love of, and involvement in, music, SAM MORTON is Samantha Morton’s first ever artist project. The collaboration came about after she appeared on Desert Island Discs in October 2020 and Russell happened to be listening. He was struck not only by her song choices (including a shared love of one song in particular: ‘I Remember’ by Molly Drake) but by the way the music weaved through her lived experiences. The pair connected and corresponded, swapping ideas, sketches and stream-of-consciousnesses. Finally, months later, they met in the studio and engaged in a period of spontaneous, intense and open-ended collaboration, one which proved to be a cathartic musical process for both parties. Daffodils & Dirt, completed during 2023, is the captivating result.

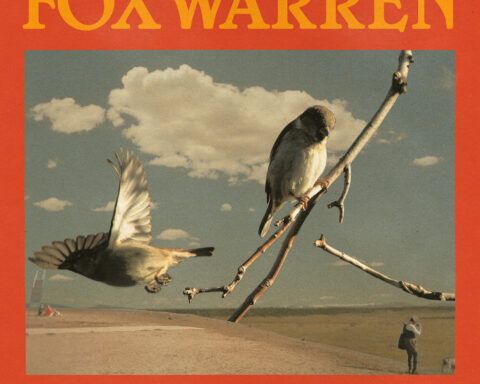

Available digitally and on CD, LP and exclusive indie-store yellow vinyl LP, Daffodils & Dirt is available to pre-order here. The album cover artwork features an archive photograph from acclaimed British-American photographer and visual artist Nick Waplington, who documented life on Nottingham’s Broxtowe Estate at the same time Morton was growing up there in the mid-1980s.

To celebrate the news, SAM MORTON today also release new single, ‘Let’s Walk In The Night,’ from the album. A kind of spectral, otherworldly reimagination of UK street soul, ‘Let’s Walk In The Night’ is accompanied by a video directed by Samantha Morton herself. Filmed on location at Nottingham’s annual Goose Fair, it’s the second music video Morton has directed from the project, following her video for (and lead role in) ‘Cry Without End‘ earlier this year.

Watch the ‘Let’s Walk In The Night’ video

1. Highwood House

2. Hungerhill Road

3. Purple Yellow

4. The Little White Cloud That Cried

5. Kaleidoscope

6. Cry Without End

7. Broxtowe Girl

8. Let’s Walk In The Night

9. Greenstone

10. Double Dip Neon

11. The Shadow

12. Loved By God

SAM MORTON, Daffodils and Dirt Biography

From the first held-down yet haunted notes of Highwood House – a wail that repeats itself and a sombre piano, like a church bell tolling – you know you’re in a place that is precarious and genuine. It’s late at night, and cold, and there’s the smell of fear and despair. Something’s being longed for, something has been lost. Samantha Morton speaks carefully, her voice close up, as if she’s confiding in us. As if we’re a stranger she met by chance on a dark road in the rain. We’re someone she can talk to. Someone she has to talk to. Because there’s no one else. On the second track, Hunger Hill Road, she begins to sing, the husky innocence of the vocal floating above a distant mellotron and percussion that seems to stumble, like the footsteps of someone out of it or drunk. There’s an uncanny authority about Morton’s voice, despite its ethereal quality, something gritty and determined, but it would feel like a lullaby were it not for the brutality and loneliness of the lyrics. “Hug me while I cry.” “The smell of piss.”

I think it was one of the thirteen remarkable women who appear in the Charles Atlas/Antony and the Johnsons documentary Turning who said, “There’s so much injury in growing up”. Samantha Morton wouldn’t disagree. During her childhood in Nottingham, she rebounded from one children’s home to another, sometimes living with foster parents, sometimes sleeping rough, everything she owned in one small plastic bag. In Daffodils and Dirt, though, Morton does more than merely draw on her troubled past. At times, she seems to be back there, inside it – music as an out-of-body experience, music as possession. She might be using her natural singing voice, but it often feels as if she is actually inhabiting her teenage self. As if somehow, in the mystical act of singing, she has morphed into the girl she once was. Dreampop, but with a whisper of The Exorcist. “The spookiness is inherent in what Sam does,” says

Richard Russell, though he also recognises that he has a certain spookiness of his own. “A few years back,” he goes on, “I was making musical sketches to play to an artist I was working with. One day, when I was in the studio, listening to the sketches, the engineer said, ‘Why’s all your music so frightening?’”

If there’s a track that captures Morton’s naked authenticity, it’s Cry Without End, which appears midway through the album. Acapella for the first two verses, her mouth right up against the mike, this is the closest thing the album has to a love song. It feels like the obvious single too. The watery piano. The CR78 drum machine like a sleigh bell or a cicada, bright and insistent. The crisp, almost harpsichord-like acoustic Gibson that breaks in halfway through. Laura Groves’s wistful, heavenly backing vocals. And then the instant, seductive hook of the chorus. Morton’s voice is so dreamy that it almost disappears at times into pure breath, and then a soft sound at the end, like someone turning over in a bed. Underpinning everything is Russell’s gift for emptiness and depth. Reared on 80s hip hop, he once claimed that the word ‘spartan’ guided his creative process. If the singer is a tightrope-walker, Russell is the air beneath, that yawning space that makes us realise how daring the act of tightrope-walking is, and how miraculous. Russell’s soundscapes, so thin and yet so rich, are the perfect setting for Morton’s delicate vocals and fierce feeling. “SAM MORTON isn’t me,” she’s eager to point out. “It’s the band name. We’re a duo.”

It’s an unlikely collaboration, but some things are meant to be. In October 2020, in the eerie, unnatural hiatus between two Covid lockdowns, Oscar-nominated actress Samantha Morton appeared on Desert Island Discs, and music producer, Richard Russell, happened to be listening. He was struck not only by the tracks she chose – “They were so connected to things I’m into,” he says.

“The randomness was my kind of randomness” – but by the way she talked. “There was a toughness and an openness that spoke to me. A positivity.” Russell contacted Morton through a mutual friend, the director Chris Cunningham, and a correspondence began, with no thought other than to include Morton on his latest Everything is Recorded project. For the next few months, Russell sent musical sketches to Morton, and Morton sent him words in what Russell calls “a remote, back-and-forth, really quite abstract process”. “Poor Richard,” Morton says. “Wherever I was, whenever something triggered me, I’d just go stream-of consciousness…Everything that Richard has ever received from me hasn’t been thought out or planned or edited or analysed. It’s just bleugh. Send. But it’s all going into a pot…like a cauldron of energy and vibes and words.”

By the time they met at Russell’s studio, The Copper House, in early 2022, there had been what Russell calls “a combined build-up.” Morton wasn’t hoping for anything. “I thought we were just having a bit of fun,” she says. “I didn’t have any expectations. I didn’t even know what it was. I was being invited and allowed to be creative in a way that I’ve never been invited into before.” She pauses. “The feeling felt like I’ve been silenced all my life, and then somebody said, You’re allowed to speak.”

After that, according to Russell, “an other-worldly amount of stuff happened in a very short space of time.” The experience was revelatory for Morton. Not only had she dreamed of being a singer when she was in care – “I honestly thought I was Annie at one point,” she says with a laugh – but she was being offered a freedom that she had never come across, certainly not in her working life as an actor. “The environment that Richard operates in is one of absolute safety,” she says. “It didn’t feel like there were any limitations.” Russell remains astonished by the way Morton adjusted to the process. He says, “The thing I loved about making this record was, Sam’s feedback and musical judgments were so acute. She was able to make such incredible calls about a side of it that was my job. We were really producing each other. That was what was happening. I felt like she was able to understand what I was doing better than anyone I’ve ever worked with.” Morton explains it like this: “Without sounding like an absolute fucking twat, there’s this waterfall…Let’s say creativity is like a waterfall, whether you’re taking a photograph or writing words or using sounds…I see them all in the same waterfall. It comes from the same part of my heart.”

The first song to emerge – Purple Yellow – begins with an intake of breath that Russell snipped out of an I-phone voice memo Morton sent him early on. It’s the kind of breath you take before you go under, not knowing if you’ll ever surface again. In Russell’s hands it becomes percussive, creating an atmosphere that’s ghostly, claustrophobic, slightly padded-cell. Since the song deals with Morton’s father, who was, in her words, “a cross between an angel and a devil”, she still struggles with the idea of it. Russell says, “My feeling was, she doesn’t like it because it’s so openly naked and vulnerable, but the vocal’s great. It’s a beautiful piece of art. Anyone I play it to responds viscerally to it.” Despite a feeling of exposure, Morton had faith in Russell’s judgement. Still, she’s adamant about one thing: “Some of the stuff is autobiographical,” she says, “but some of it isn’t. It’s Richard and I getting excited by subject matter – a

death, rebirth – and obviously bits of my past come into that…It’s important to know that I would share things with Richard and he would add to that, or take things away. Find something new. It was like we were able to fuck with it, which is amazing. So it’s not just, ‘This is the past I’m singing about’. It’s not. It’s been turned into fiction – a narrative.” Russell agrees. When he went to a Van Gogh exhibition at Morton’s suggestion, it suddenly struck him that what they were doing was creating a portrait of Sam together. “It’s partly a self-portrait, by Sam,” he says, “and partly a portrait of Sam, by me.” In working with Russell, Morton has been able to inhabit the pain and dysfunction of her childhood and make something entirely new of it. As Louise Bourgeois once said, “We either die of the past or we become an artist.”

On tracks like Greenstone, which is driven by a live electric bass that seems to glow and spanner-on-an-oil-drum percussion, and Let’s Walk in the Night, which features Alabaster de Plume’s quavery, ancient-sounding saxophone, Laura Groves’s doo-wop backing vocals, and a soft but compelling industrial pulse, there is often the sense that something could be unleashed, but restraint and delicacy win out. As on Radiohead’s Kid A, the burying of tunes or beats speaks to the power of the material, the trembling emotion at its core.

These are intimate songs. They have been hauled up from the deep vault of the heart. Even on the cover of Johnny Ray’s Little White Cloud that Cried, Russell makes sure that Morton’s breathy resilience is the focus. The danciest track on the album is Double Dip Neon, where the voice still floats, but the beats are more upfront, more urgent. There’s a sample from Sterling Void’s classic, It’s All Right.

There’s a dub bass too. Russell’s subtle homages to house. “Sam said we should make a rave tune,” he says. “I don’t make music like that any more, so I was a bit dubious, but then Sam encouraged me, and I tried it, and it felt great.”

The songs on Daffodils and Dirt are scary, gorgeous, fragile, heart- jangling compositions. Shamanic too, as if by singing Morton can exorcise the past. Repurpose it. Make gold of all that murk. A sense of hope or self- belief lifts phoenix-like out of all the nervy, aching darkness, a reminder that true strength is often to be found in an acknowledgement of extreme vulnerability. In the last track, Loved by God, written as a prayer when Morton was only seven or eight years old, we’re listening to a mystic, someone who is aware that she’s part of something greater than herself, a power that is immanent, intensely present in the here and now. It’s no surprise to discover that she believes “that singing – the human voice – is a direct link to God.”

As collaborations go, you couldn’t ask for something more unforeseeable or more sublime, and it speaks not only to Morton’s bravery and the unerring quality of Russell’s instinct, but to their individual artistry, and to the creative sparks that fly between them when they’re together, something Pierre Guyotat once described as “the duel with beauty, which is the writing of a work.” Ali Campbell’s presence as a vocalist on Broxstowe Girl is symptomatic of the fairy dust that descended on the project, as he has always been one of Morton and Russell’s musical heroes. “To me, this feels like a dream come true,” Morton says, “and that’s why I feel utterly blessed. Fucking hell, that happened. That happened to me.” Russell is equally euphoric. “It was so exciting, the making of it,” he says. “It felt like doing something for the first time. People struggle to have that feeling.”

Rupert Thompson, October 8th 2023

SAMANTHA MORTON INSTAGRAM